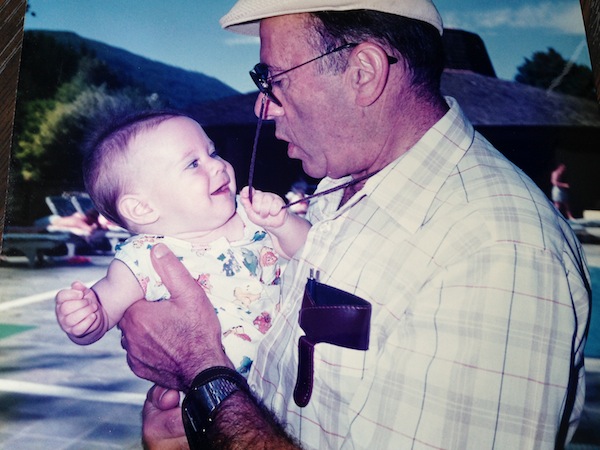

The writer with her grandfather, George Wertman. (photo from Becca Wertman)

I believe it was in Grade 6 at Vancouver Talmud Torah that we had to do a project about a “Jewish hero.” I remember other students wrote about Theodor Herzl, the founder of modern Zionism; Golda Meir, the first female Israeli prime minister; and Hannah Senesh, the Palmach paratrooper who was executed by Nazis while attempting to save Hungarian Jews. I wrote about my zaida.

My zaida, George Wertman, was born on May 17, 1921, in Lwów, Poland (now Lviv, Ukraine), and passed away on March 25, 2019, in Vancouver. He was a Holocaust survivor, yet that alone is not why I consider him my hero – it is because of how he survived and what he managed to accomplish in his life.

In fall 1941, Zaida was taken to a forced labour camp, Camp Winniki, where he became an assistant steamroll engineer, enslaved to build roads for the Nazis.

Zaida always marched in the first group of three during the 12-to-14-kilometre trek from the camp to the work site. One day, he lined up in the third group and, on that same day, two individuals escaped the camp. As was the “camp policy,” three people were shot for every person who escaped. The SS officer selected the first two rows and took them into the forest to their deaths. Zaida survived by sheer luck.

On other occasions, it was more than just luck that saved his life – it was his reputation as being a hard worker. In his second year in the camp, Zaida became ill with typhoid and was taken to the camp’s infirmary. An SS officer and a Ukrainian policeman came to the infirmary to select sick Jews to be shot for, as Zaida explained to me, why would Nazis spend scarce resources on healing sick Jews? The SS officer yelled to my zaida, “Out!” but the Ukrainian insisted that Zaida was his best worker and to save him.

In July 1943, Zaida’s determination to live motivated him to run when an SS officer came to his barracks in the middle of the night and told him to get dressed and, again, “Out!” Zaida preferred dying on his own terms – while doing everything he could to survive – and, therefore, jumped out of the window and ran. He ran through puddles to trick the scent dogs and eventually outsmarted the Nazis, managing to escape to “safety.” The rest of the camp was liquidated and sent to their deaths.

“Safety” meant reuniting with my great-grandfather in his hiding spot in a secret room located in a building where German officers lived. For one year, Zaida spoke in whispers and did not see the sun.

Zaida was liberated in summer 1944, but his story of survival by no means ended there. He met my grandmother (my baba, who I call Babi), and she, Zaida and my great-grandfather began a “business” of necessity – smuggling goods across one European border and the next. They would hollow out suitcases, fill the frames with gold and give them to my 20-year-old grandmother to carry across the border.

They eventually made enough money to get visas to Canada and, in July 1949, arrived in Vancouver.

The money they had made in Europe was invested in property, including a piece of land bought from the Canadian Pacific Railway that became my dad’s childhood (and current) house and a property that housed George Wertman Ltd., Zaida’s coat hanger factory.

Zaida worked extremely hard to succeed in Canada, making wire coat hangers and doing everything to ensure that his three children and eight grandchildren would never have to suffer.

His retirement largely consisted of wining, dining and drinking coffee throughout Vancouver. From the age of 91 to 96, he could be found daily at the Hotel Georgia’s Bel Café sharing a grilled cheese sandwich with Babi.

As the granddaughter of Holocaust survivors, I have unique childhood memories. I remember my family parking at least a 15-minute walk away, usually more, from the best restaurants in Vancouver in order to not pay for parking and to “save a buck”; of eating chicken soup in bowls of gold-rimmed china that my grandparents brought from Allied-occupied Germany; and of always asking Zaida to tell me stories, like the ones above.

In Zaida’s Holocaust survivor testimony to the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, he explains that his philosophy is that you “have to work to get somewhere” and that he believes in “honesty, hard work and, once in awhile, if you can do a mitzvah,” do it. Indeed, hard work saved his life and being an honest businessman in Canada allowed him to give his family everything they needed.

As Zaida also instructs in his testimony, “Try to make a better world. If you cannot make a better world, do not make it worse.”

This is why he was, is, and will always be, my hero and my inspiration for how I live. I hope his story, summarized here, will inspire others as well. May his memory be a blessing.

Becca Wertman grew up in Vancouver and currently lives and works in Jerusalem.