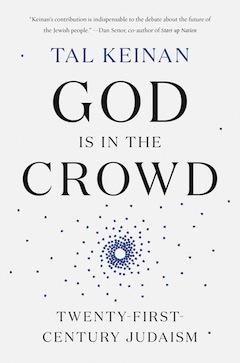

There are many puzzling things about the book God is in the Crowd. It is published by a prominent Canadian publishing house (McClelland and Stewart) but was printed in the United States. It is written by an American-Israeli, Tal Keinan, who was the beneficiary of a first-class prep school education, Exeter, in New England, and was the recipient of an MBA from Harvard. His book is, in some ways, a hodgepodge of personal reminiscences of life in a broken family in America, encounters with various strands of American Judaism, and a passage to Israel, where he beat the odds and became a fighter pilot in the Israeli air force.

Keinan’s English prose style is exceptionally moving, literate and attractive. This is especially true in the section where he describes the rigours of his training and, later, in a discourse filled with self-reproach when he discovers that he has bombed the wrong target during an attack in Lebanon. The author’s thoughts on flying and his lyrical, almost poetical, style reminds this reviewer of French author Antoine de Saint Exupery’s book Night Flight, in which the rhapsody of flying is celebrated with fervour and a certain panache.

Among the many subjects that Keinan tackles in this strangely compelling personal journal is the current configuration of Israel’s population, which he sees as a tripartite collective composed of territorialists, theocrats and secularists. Although his predilection is for the third category, he has much to say about the religious origins of Israel and the Jewish people. In fact, he credits Rabbi Yehudah Hanassi with resuscitating Judaism after the destruction of the Great Temple of Jerusalem through his compilation of the Mishnah in the first century of the Common Era.

Because he finds the world Jewish community dangerously fragmented, and Israel unresponsive to smaller start-up enterprises, Keinan, who founded Koret, a fund for small businesses, and who is active in the Steinhardt Foundation (Birthright), proposes a very ambitious program to galvanize young Jews through, among other things, a vibrant Jewish summer camp experience, higher education in Jewish sources and a commitment to financial obligations to sustain these three essentials. His ideas are complex but he does provide extensive details to buttress his argument.

Those who look for logical and sequential ideas in this challenging book will be somewhat disappointed in its title, which claims that “God is in the crowd,” an idea the author promotes in ways that are not entirely clear despite the praise heaped on Keinan by six distinguished commentators whose views are on the back of the book jacket, as well as an endorsement on the front of the jacket by Lord Jonathan Sacks. This reviewer must have missed something in his reading of the chapters in which the author talks about “crowd wisdom.”

Those who look for logical and sequential ideas in this challenging book will be somewhat disappointed in its title, which claims that “God is in the crowd,” an idea the author promotes in ways that are not entirely clear despite the praise heaped on Keinan by six distinguished commentators whose views are on the back of the book jacket, as well as an endorsement on the front of the jacket by Lord Jonathan Sacks. This reviewer must have missed something in his reading of the chapters in which the author talks about “crowd wisdom.”

Based on an experiment to discern how many gum balls were displayed in a large glass container at one of his investment shows, Keinan suggests that the collective guesses were closer to the correct number than individual number choices and, from this observation, the author leaps into generalizations about how Jewish unity among Diaspora Jews was secured by “crowd wisdom,” no matter the geographical, religious or cultural disposition of the disparate communities. Keinan tends to annoy the reader by discoursing on this idea and then abruptly changing his agenda by addressing other concerns, and then returning to the “crowd wisdom” theme.

Despite the ambiguities in his discussion of “crowd wisdom,” Keinan has one section in this autobiographical memoir that merits high praise. During his service in the Israeli air force, the author developed a friendship and admiration for a fellow pilot – a secular kibbutznik who was a model for Keinan both in terms of aeronautics and moral compass. The friendship continued after their air force service and then, one day, years later, Keinan saw that his old buddy was wearing a kippah. Keinan writes with a heavy heart that the longtime friendship dwindled slowly and finally dissolved.

Arnold Ages is distinguished emeritus professor at the University of Waterloo in Ontario.