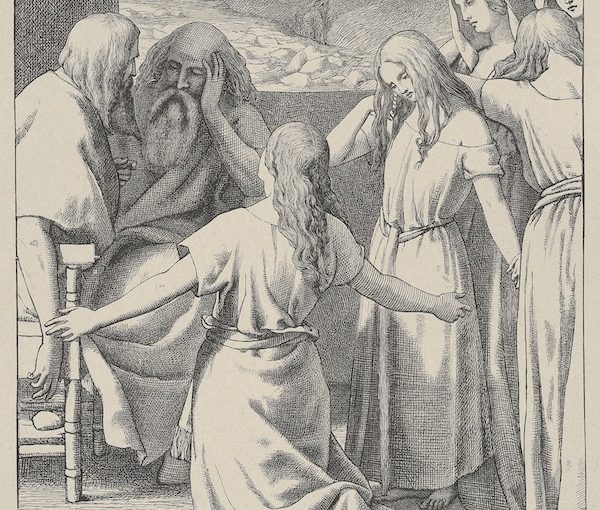

The Daughters of Zelophehad by artist Frederick Richard Pickersgill, engraver Dalziel Brothers, 1865-1881. (photo from metmuseum.org)

“A cobbler passed by the window of Rabbi Levi Yitzhak, calling out: “Have you nothing to mend?!” The rabbi began to cry: “Woe is me! Rosh Hashanah is almost here and I have not yet mended myself!” (Zichron Ha Rishonim)

According to Rabbi Kruspedai, in the name of Rabbi Yohanan, three books are opened on Rosh Hashanah: one for the wholly righteous, one for the wholly wicked and one for most of us, those in between. The wholly righteous are inscribed and sealed in the Book of Life; the wicked in the Book of Death; and the rest of us are held suspended until Yom Kippur, when we are judged worthy or unworthy. The zodiacal symbol for the Hebrew month of Tishri is, fittingly, a balance – the scales of justice.

When Creation was established, but still incomplete, humans had an important role – to fill the earth with life and to sustain life at the highest level (Genesis 1:28). We became a partner with the Creator in tikkun olam, perfecting the world.

Women are not relegated to a minor position in this task. As Rosh Hashanah approaches, Jewish women reflect on their role, knowing that they have more to do than merely bake honey cakes, send out Shana Tova cards and light candles.

Since coming to live in Israel five decades ago, I have felt the need for a deeper, more spiritual aspect. Every type of Jewish woman is represented in Jerusalem, from the ultra-Orthodox matron to the professional modern religious woman; from the Reform woman rabbi to the completely secular woman who sees any kind of ritual as nonsense. Each has her convictions and will act on them accordingly.

Having begun my life as a fairly assimilated Jewess, I fall somewhere in the middle. I consider myself a modern, observant woman, although I fall short of my daughters, who cover their hair and have studied Talmud, Mishnah and Jewish philosophy at a level of commitment to Judaism I probably will never attain. Yet, I am not totally ignorant, nor have I been left entirely unaffected by the feminist movement. I do believe that the Torah was given by G-d at Mount Sinai and one may not change it even one iota. But neither am I satisfied to fulfil the prayer of the pious father at his daughter’s birth in the Middle Ages: “May she sew, spin, weave and be brought up to a life of good deeds” – especially as the first three skills are completely beyond me!

I want to find a comfortable spiritual niche for myself within the framework of halachah (Jewish law). I have no desire to don tallit or tefillin to make a feminist statement, yet I know there are possibilities that exist for the Jewish woman that give her a place beyond catering to the family’s gastronomic needs when the Days of Awe come round. Many opponents of orthodoxy contend that women are not honoured in Judaism, despite the deep reverence for Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. My namesake, Dvora, the judge and prophetess, is also greatly honoured for her political, moral and religious leadership.

There are contemporary Orthodox women who have widened the halachic barriers by challenging practices of separate synagogue seating, and questioning the right of women to be called to the Torah and to be counted in the minyan (traditionally, the minimum 10 men required for communal worship). These privileges do not unduly attract me – if they did, I would attend a Conservative or Reform synagogue. I am not even tempted to join a halachically permitted women’s “minyan” – I rather enjoy my silent communion with G-d and don’t feel it necessary to see everything that is going on. G-d hears Jewish women’s pleas, as He did in the case of the childless Sarah, Rachel and Hannah and the landless daughters of Zelophehad.

I don’t yearn for religious parity with men. Not everything in life can be equal or fulfilled at every given moment. Demands for personal gratification and unreal expectations can destroy relationships in the secular sphere also. Blu Greenberg, a pioneering Orthodox feminist and writer, has defined “time, energy, a measure of sacrifice and generosity of spirit” as the enemies of instant gratification and believes that one is only free within an ethical and moral structure.

With the approach of the High Holy Days, there are women who are searching for a role that will be neither insignificant nor undervalued. We are sifting through the perspectives of Jewish values, what we can welcome and what we can reject.

We will attend synagogue and listen to the shofar as men and women are obligated to do, and try to observe the period of penitence that ends with Yom Kippur. There are also tehinnot (petitional prayers; in Yiddish, tkhines) for women, written in Yiddish in Bohemia and published in Germany, Russia and Poland in the 18th century, which I would like to find and have translated. They emphasize G-d as a loving father rather than as a stern judge; the merit of the matriarchs; and define rewards in terms of pious and virtuous children. They represent a kind of folk literature, mirroring the daily life and concerns at that time in the ghetto. As it is known that many of the tehinnot were composed by women – a rare phenomenon – I think they are appropriate prayers to be added by women to the traditional ones at this time.

Mainly, I think, we should sustain our belief that women, as well as men, are made in G-d’s image. For me, being a Jewish woman largely defines who I am and what I am called to do. Our sages tell a story that, when the Torah was first given, G-d told Moses to teach it first to the women. I believe the reason – that is still valid today – was that women were the architects of the next generation, and their acceptance of it would determine whether or not future generations would continue the covenant. Surely, there is no more significant role as we approach the New Year and the Day of Judgment. May we all be inscribed for a good year.

Dvora Waysman, originally from Melbourne, Australia, has lived in Jerusalem for 50 years. She has written 14 books, and the film The Golden Pomegranate was based on her novel The Pomegranate Pendant. She can be contacted at [email protected].