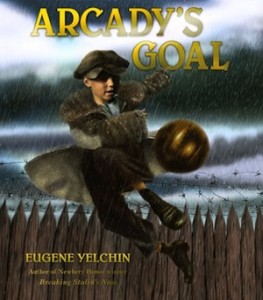

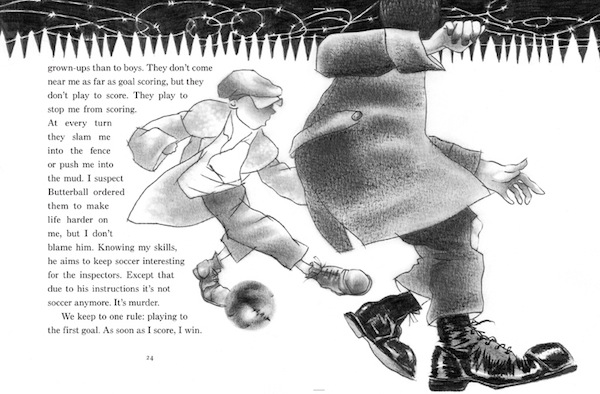

Eugene Yelchin’s illustrations are an integral part of the storytelling in Arcady’s Goal.

What a special tribute to a parent. Eugene Yelchin’s most recent children’s book,

Arcady’s Goal, started with a 1945 photograph of the Red Army Soccer Club. One of fewer than a dozen photos of his family that “survived the turbulent history of the Soviet Union,” it includes the team’s captain, Arcady Yelchin, his father.

Historical fiction aimed at kids age 9 to 12, Arcady’s Goal (Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, 2014) will hold the interest of older readers and elicit much discussion. Set in Soviet Russia during Stalin’s reign of terror, its main character, Arcady, is a feisty, self-confident 12-year-old who has lived in several children’s homes (“home” being euphemistic for camp or prison) since he was 3 years old and his parents were arrested on the charge of “participation in a terrorist organization. Preparing to overthrow Soviet power and the defeat of the USSR in a future war.”

Arcady has survived on his wits, his courage to stand up to those in authority and strength to deal with the consequences, and his incredible skill at soccer. Playing one-on-one soccer with other kids for rations, Arcady initially seems ruthless, but the act of it is revealed when he returns his winnings (“an eighth of bread, our daily ration”) to the boy he beats. And, when a group of inspectors comes to the compound, Arcady makes a deal with the director: Arcady will play whomever the director lines up and, for every win, the director will give him and the loser of the match two bread rations.

During the “games,” one of the inspectors seems especially interested in Arcady. While Arcady didn’t believe the director who, when trying to convince him to play, said there might be a soccer coach among the inspectors scouting for new talent, Arcady nonetheless starts thinking that this man is indeed a coach. When Ivan Ivanych returns to adopt Arcady, the boy thinks it’s because of his soccer talent – and that, if he fails to perform as expected, he’ll find himself back at the children’s home.

Without revealing what happens, the relationship between Arcady and Ivan is really touching. Reading how it develops, the hurdles they both have to overcome, the trust they both need to gain, the courage they both need to find, is inspiring, especially surrounded as they are by people who would do them ill out of fear or ambition – with two notable exceptions. Arcady’s Goal is a well-told story that respects its readers and doesn’t shy away from difficult material even while delivering a positive, hopeful message. The black and white illustrations by Yelchin communicate an additional depth of feeling and movement, or stillness.

Yelchin, who was born in Russia, left the former Soviet Union when he was 27. Arcady’s Goal is considered a companion novel to Breaking Stalin’s Nose (Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, 2011). Also written and illustrated by Yelchin, the 2012 Newberry Honor book centres around 10-year-old Sasha Zaichik, who has wanted to be a Young Soviet Pioneer since he was 6 but when the time comes to join, “everything seems to go awry. Perhaps Sasha does not want to be a Young Soviet Pioneer after all. Is it possible that everything he knows about the Soviet government is a lie?”

In the author’s note that follows the story in Arcady’s Goal, Yelchin writes about an experience he had in the summer of 2013 when he was at Oakland University in Michigan to speak to students who were studying Breaking Stalin’s Nose. After his talk, he caught a cab to the airport. The driver had also come from St. Petersburg. When the reason for Yelchin’s trip came up in conversation, the driver fell silent, then revealed that his grandfather had died as a result of being sent to a hard labor camp for 10 years by Stalin. “I caught myself leaning in close to hear Yury,” writes Yelchin. “He was whispering.

“And so it goes. The terror inflicted upon the Russian people by Stalinism did not die with those who experienced it firsthand but continued on from one generation to the next. It is as if anyone born in the Soviet Union continued to suffer from a post-traumatic stress disorder that has never been treated.” The Communist Party, with its preemptive strikes against people who might disagree with them, “ensured that this trauma would live on even after the demise of communism. It did so by shattering families of the enemies of the people. Their family members were denied places to live, work, permits and food rations. Children suffered the most. Infants were separated from their mothers, placed into the security police-run orphanages and often given different surnames.” Yelchin notes that everything was taken away from these children, and that children could receive the death penalty at age 12. For these and other reasons, says Yelchin, even 60 years after Stalin’s death, a cab driver thousands of miles away from Russia whispered “as he shared the fate of his grandfather, an enemy of the people.”

There is a teacher’s guide for Arcady’s Goal that can be downloaded from eugeneyelchinbooks.com/arcadys-goal.php. It is quite intriguing in and of itself, and would be an excellent resource for non-teachers as well.