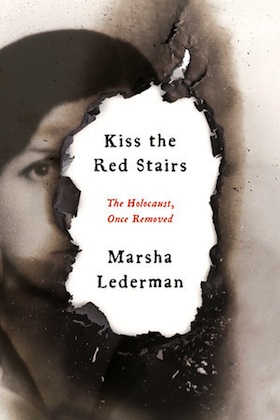

Marsha Lederman’s Kiss the Red Stairs begins in 1919, when her father was born, on erev Yom Kippur. (photo by Ben Nelms)

In the last couple of decades, researchers have identified traits that affect many children of Holocaust survivors. There remains much left to uncover, including how much is epigenetic – that is, whether and how the genes of people like survivors, who have undergone extreme trauma, work differently than other people’s – and how much might be a result of the parenting styles of people who, in many instances, were ripped from their own parents in the most brutal circumstances. The old issue of nature versus nurture, in other words.

While psychologists and scientists try to unravel those mysteries, a genre of second generation memoirs is exploring the deeply personal experiences of being raised by survivors of the Shoah. A page-turning, sometimes shocking and nakedly vulnerable volume has recently added much to the growing library.

Vancouver journalist Marsha Lederman, Western arts correspondent for the Globe and Mail, has written Kiss the Red Stairs: The Holocaust, Once Removed. The book begins in 1919, when Jacob Meier Lederman was born on erev Yom Kippur. The auspicious timing of the birth of this baby, who would grow to become Marsha Lederman’s father, portended great things.

“[T]his was an occasion, an omen – a very good one, the hugest of deals,” she writes. “This person was special, he was going to be something, do something very important with his life.”

Indeed, he did. He survived the Holocaust – the only person in his immediate family to do so and one of only 10% of the Polish Jews alive in 1939 who survived to 1945.

Marsha Lederman’s mother was also a survivor, and one who participated in Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation testimony project, video-recording her Holocaust experiences. This recording would become a touchstone because, despite the journalist daughter’s career asking questions of strangers, there were many unanswered questions in the family. This was due in part to the harrowing, abrupt response to a childish inquiry about the absence of grandparents, an early lesson that unexpected answers can have catastrophic emotional impacts.

Well into adulthood, Lederman decided to visit her mother during a snowbird retreat in Florida. But instead of sitting across the kitchen table learning about her mother’s darkest moments, she was instead living one of her own – delivering her mother’s eulogy. She had waited a day too long to fly south.

Lederman’s book is the story of a family – two families, really. A family that in some ways never came together quite right, the author’s birth family with its silences about the past, and another that fell apart, that of her marriage. Kiss the Red Stairs, in fact, is a sort of applied case study in second generation (shorthanded “2G”) neuroses, as they distort the author’s reactions and coping mechanisms in a time of personal crisis.

Lederman’s book is the story of a family – two families, really. A family that in some ways never came together quite right, the author’s birth family with its silences about the past, and another that fell apart, that of her marriage. Kiss the Red Stairs, in fact, is a sort of applied case study in second generation (shorthanded “2G”) neuroses, as they distort the author’s reactions and coping mechanisms in a time of personal crisis.

As her marriage collapses, Lederman recognizes, on the one hand, that her responses may not be commensurate with actual events but are exacerbated by a lifetime of fears around loss and abandonment. On another hand, the undeniable anguish of her marital breakdown evokes an added burden of guilt, her own trauma juxtaposed with her parents’ experiences. Given what their mothers and fathers endured, do children of survivors have a right to feel the pain that other people seem to validly experience?

Lederman acknowledges that she was always ready for everything to fall to pieces. She inherited – or developed – an existential pessimism and a catastrophizing worldview: “The glass wasn’t just half-empty; it was half-full of poison,” she writes. “Or Zyklon B.”

The history that has formed Lederman’s identity was not imprinted on her at home only. It was in the zeitgeist of her coming-of-age as a young Canadian Jew in the 1970s and ’80s.

“The slogan ‘Never Again’ was drilled into us, implying – to me, anyway – that there was always the potential for an again, for another catastrophe. What would we do when the Nazis came back and came for us, like they came for our parents?

“This happened to us. This could happen to us again. I was one of the us. On some level I believed, from a very young age, that this could happen to me. I understood the need to be on guard, that we weren’t really safe. We needed to be on alert. Have a plan.”

For whatever were their good intentions, the organizers of a youth trip to Israel reinforced Lederman’s anxieties. Intending to instil in the participants the need for one solitary Jewish state in the world, they reminded their young charges that, in the absence of Israel, Jews would have nowhere to go should the need arise, “if the world once again turned on – or turned its back on – the Jews.”

She doesn’t disagree with the premise. “But the exercise scared the hell out of me. Don’t be so comfortable in that Canada you think of as home; you never know what could happen.”

That awareness of the unimaginable human capability for inhumanity had imprinted on her to the extent that everyday life became a gauntlet of inevitable disaster, misery the preordained endpoint of any happiness. When her marriage broke down, her reaction was extreme, “As if divorce, for instance, were some kind of death camp.”

Having consciously tried to eradicate (second-hand) Holocaust memory from its constant intrusion into her mind, Lederman finally faces the core question of her life, and of the book: “Could I possibly be a victim of the Holocaust, once removed?”

Now a mother, her obsessive worry has a new object, not only in terms of the world into which that child was born, but the potential for epigenetic inheritance. Will the baggage of the past be passed along to another descendant of survivors?

At the same time, Lederman is careful not to ascribe her challenges to the overburdened couple who raised her.

“I am not comfortable blaming what happened to my parents – and, in effect, blaming them – for my little problems. It feels self-indulgent, unfair and actually untrue,” she writes. What they accomplished after the war was almost as miraculous as their survival during it. “The fact that after such tragedy my parents were able to build new lives – purchase and set up a home, go to night school to learn English, buy a business, raise children – seems astonishing to me, as I contemplate it all as an adult. How on earth did they manage to do it, manage to be so normal?”

She quotes Elie Wiesel who, in 1984, told children of Holocaust survivors: “That your parents were not seized by an irrepressible anger … remains a source of astonishment to me. Had they set fire to the entire planet, it would not have surprised anyone.”

Elsewhere in Lederman’s book, Wiesel appears again, seemingly underscoring the legitimacy of second generation complexes by noting that it was they, not their parents, who were the ultimate target of Hitler’s plan.

“You were the enemy’s obsessions,” Wiesel told the children of survivors. “In murdering living Jews, he wished to prevent you from being born.”

Lederman confronts the reader with things she has learned from research, rather than from firsthand experience or from stories her parents shared (because they didn’t). The Holocaust experiences of her parents may be the impetus for her lifelong sense of danger, she seems to suggest, but the larger history of that era should be a warning shot for all humans – because it was humans who perpetrated everything that happened to her parents and to the millions of others of the Nazis’ victims.

In one of several graphic segments, she demands that the reader ponder how ordinary people could throw babies in the air and practise a merciless form of skeet shooting.

There are other psychological conundrums in the book. Reading her father’s journal of a trip back to Europe, Lederman confronts what reads like a cognitive rupture: her father’s love for and comparatively happy memories of Germany.

Rather than remain in Nazi-occupied Poland, young Jacob audaciously crossed into the belly of the beast, into Germany, posing as a Polish peasant boy, and got work as a farmhand, surviving until the end of the war. As a result, he took a perversely positive view. In a travel diary entry, he wrote, “I had a wonderful exciting day and my motto stands again forever: I will never forget you Germany and the peace and security I found here among these fields, meadows and trees in those murderous inhuman times of the year 1942.”

Of all the happenstances in the book – some life-altering and, in several instances, life-saving – there is a particularly poignant one that happened on her father’s trip back to his hometown. On that trip, her father found out that his parents had left a letter for him before they had been evacuated from the ghetto and shortly thereafter murdered.

“A Polish woman who lived there at the time, or moved in after the liquidation – I’m not sure which – had come into possession of that letter. There were photos in this packet and some other family keepsakes,” she writes. “The woman said she had held onto these items for a long time, but after so many years without word, she lost all hope that my father had survived; she figured nobody from the family had. She threw the packet away.

“What was that like for him – to learn that his parents had left him something: a declaration of their love, a wish for his future, some unknown secret, an explanation of what was happening to them? And to learn that those things once touched and left for him by his parents – a written document, photographs, who knows what else – proof that his parents had existed, evidence of their love – had survived, only to be discarded?”

On her own ventures to the blood-soaked continent, Lederman is reminded that the past has not passed. She sees antisemitic graffiti on abandoned synagogues, Polish youths giving obscene gestures to participants during the March of the Living. Lederman and four family members are paying tribute at a Holocaust memorial while a group of boys nearby chant something in Polish, something menacing that included one term she recognized: “Auschwitz-Birkenau.”

“It didn’t sound like they were expressing their condolences,” she writes.

After a lifetime of mostly solitary rumination and fears, Lederman has several epiphanies during the World Federation of Child Survivors of the Holocaust annual conference, held in 2019 in Vancouver. Here, she finds others who share her view that “the other shoe is always about to drop and the world is not safe”; “being plagued with obsessive doubt”; “a heightened ability – one might call it a curse – to observe and engage others”; “A constant expectation that someone is going to get you.”

There, she finds she is not alone.

“I had found my people,” she writes.