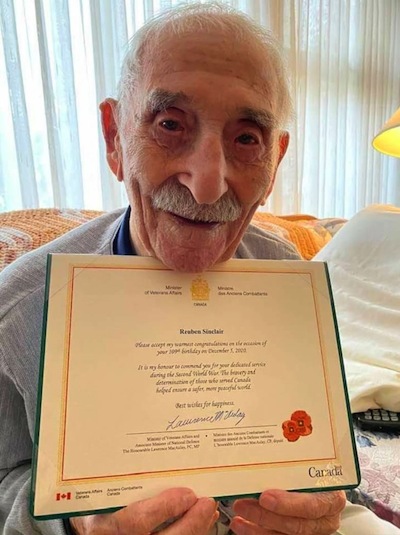

At 109, Richmond resident Reuben (Rube) Sinclair might be Canada’s oldest Second World War veteran. (photo from Reuben Sinclair)

A Richmond resident is almost certainly Canada’s oldest Second World War veteran. Reuben (Rube) Sinclair received a special recognition on Remembrance Day, though, because of confidentiality issues, Veterans Affairs Canada can’t confirm he’s the oldest service member. But, at the age of 109, basic statistics suggests that, if Sinclair isn’t the oldest, he’s got to be close.

The centenarian spoke with the Independent virtually via Zoom about his life and what advice he might have for aspiring super-seniors like himself.

Sinclair was born in 1911 on the family farm near Lipton, Sask. Lipton was one of many “colonies” created by Baron Maurice de Hirsch in Canada, Argentina and Palestine to resettle oppressed Jews from Europe. Sinclair’s father, Yitzok Sinclair (born Sandler), traveled from Ukraine, via Liverpool and arrived at Ellis Island Jan. 4, 1905, on the SS Ivernia. He made his way to Saskatchewan, where he was given land by de Hirsch’s Jewish Colonization Association. However, the land was poor and so the newcomer worked for the Canadian National Railway long enough to save up and buy a better plot and build a house. When he was settled, he sent for his wife, Fraida (born Dubrovinsky), and their two young sons.

Reunited in Lipton, the family grew to include not only Samuel and Sol, who were born in the old country, but the only sister, Clara, then Rube and the youngest, Joe.

The last survivor of his birth family, Sinclair has fond memories of the farm life. He and the other two youngest did chores while the older two headed to university. Samuel became a medical doctor and Sol was a professor of agriculture at the University of Manitoba.

“There was a whole colony of Jewish families,” Sinclair said. “My parents had one of the largest farms – 16 quarter-sections [more than 2,500 acres]. I remember we had 42 horses. We had milk cows. I had my jobs. My job was to go collect the eggs from the chicken house and, when I was 12, I was already driving our car.… Always things to do on a farm.”

Yitzok donated a few acres to the community and helped construct a school, which doubled as a synagogue. On Shabbats and Jewish holidays in winter, the boys would sleep in the hayloft so the local men could stay in the house and not walk home in the freezing Saskatchewan weather.

“My father was a leader in the community,” he said.

Sinclair joined the Royal Canadian Air Force during the Second World War and was stationed in North Battleford, Sask. In the days before radar was commonplace, he taught Allied pilots how to take off and land in the dark using a “standard beam approach,” which involved a navigation receiver that allowed the pilot to line the aircraft up with the runway when preparing to land.

“In the air force barracks, I was on the top bunk,” he said. “I always got the top bunk because the younger generation would come home drunk and I wouldn’t sleep in the bottom bunk.”

One day, he encountered a barrack-mate in tears. Sinclair recalls the conversation: “They’re sending me to Vancouver, he said, and my family is all here around Brandon, Manitoba. So I said, that’s no problem. When they want a person to go to Vancouver, they don’t care who the person is. Vancouver wants one person. So, I said, don’t cry. We’ll go see the commanding officer. I told him that my wife has got family in Vancouver and I’d be glad to go instead. He said they don’t care, all they want is one person. So, I was the person who went to Vancouver at that time and I’m still here,” he recalled with a laugh.

Joe, the youngest of the five siblings, had served in the army and after the war joined Rube in British Columbia. They started Sinclair Bros. Garage and Auto Wrecking, in Richmond, just across the two old Fraser Street bridges from Vancouver.

“My job was to go out and find old cars and we had a tow truck,” Sinclair said. “I’d bring them in and my younger brother would wreck them. We opened a wrecking company.” They also bought surplus army vehicles to fix up and sell.

The business soon became a sort of family compound. A small house adjacent went up for sale and the Sinclairs bought it, bringing parents Yitzok and Fraida to the coast. Then sister Clara and her husband Morris Slobasky bought a general store that was next door.

Because of his wartime experience, Sinclair developed migraine headaches and was told to go to a drier climate. He thought Arizona sounded good, but his wife, Ida, had siblings in the Los Angeles area and a brother-in-law offered him a job in a furniture store in Anaheim.

In 1964, Rube and Ida packed up the three kids – Nadine (now Lipetz), Karen and Len – and moved to Southern California.

“He put me in charge of the furniture store,” Sinclair said of his brother-in-law. “I knew nothing about furniture, but I learned pretty quick.”

Soon he was in business for himself again.

“Then my boss that I worked for in Anaheim, his wife wasn’t very well and she spent a lot of time in Palm Springs,” Sinclair recalled. “So, he said, instead of me going back and forth, I’ll move to Palm Springs and you can have the store, just pay me for the inventory.”

In 1994, Ida had a stroke and the couple moved back to British Columbia. She passed in 1996. Rube still lives in their Richmond condo.

Rube and Ida were active in their communities. In Los Angeles, they raised more than a million dollars for City of Hope, a cancer hospital and research facility. Both were active members of Schara Tzedeck Synagogue here, he especially in the Men’s Club, and he is proud of his lifetime honorary membership in the shul. In addition to their three adult children – Nadine is in Vancouver; Karen and Len in California – he has six grandchildren, 16 great-grandchildren and one great-great-grandchild.

Asked if he has any advice for others, Sinclair didn’t hesitate.

“That’s easy. I always say, if you have a problem, don’t worry; you’ll lose your hair. Fix it. If you have a problem, fix it. Don’t sit back and worry. Worry is not going to help.”

Any bad habits?

“I don’t think so,” he said after a thought. “I spent most of my life working and, in my spare time, working for people less fortunate. That was my enjoyment in my spare time.”

Two years ago, the City of Richmond named Sinclair an “honoured veteran.”

Recalled daughter Nadine: “He was part of the Remembrance Day service in Richmond and they made a big deal about it. They sent a limo and he sat with the mayor and the Silver Cross Mother. They gave him a wreath and then they walked him around. He was up on the dais with the mayor and the head of the RCMP as the soldiers all walked by. It was a very big deal for him.” Last Remembrance Day, he received a certificate from Veterans Affairs.

If, by some chance, Sinclair is not

Canada’s oldest veteran of the Second World War, he seems determined to attain that title.

“I’m not going anywhere,” he said. “I still have some unfinished business.”