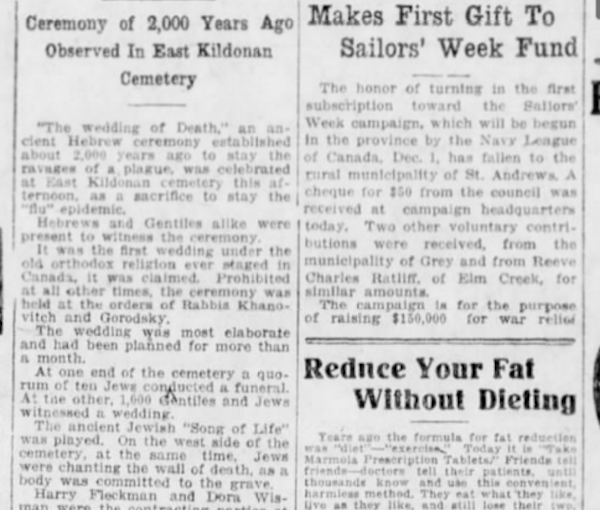

According to the Nov. 11, 1918, Winnipeg Tribune, Rose Schwartz and Abraham Lachterman were married in a plague wedding in Winnipeg, Man. More than 1,000 people attended, Jews and non-Jews.

Relatively early in the evolution of the coronavirus pandemic, in March 2020, there was an unusual wedding in Israel. The ceremony took place in Bnei Brak’s Ponevezh Cemetery. The bride (kallah) and groom (hatan), both orphans, had not previously known each other. Even in the ultra-Orthodox community, where there is a range of arranged to forced marriages, such an event – a black (shvartse) or plague (mageyfe) wedding – is extremely rare.

Written accounts of plague weddings date back almost 200 years, to eastern Europe. In these accounts, one learns that “targeted” couples were people who were orphaned, homeless, or had physical or intellectual challenges. In these scenarios, the community contends it is doing a favour to these brides and grooms, as it assumes that the couple has only a slim chance of marrying otherwise.

Had this contemporary couple under the wedding canopy been free to choose, or had they been coerced or something in between? Were they promised something to get them under the chuppah? Maybe they were gifted, respectively, their wedding dress and suit? There again, however, these outfits could have come from a wedding gemach, a charity warehouse from which people borrow items of clothing. Or perhaps, as was customary in earlier times, some well-to-do community member offered to “set up house” for them.

One thing is clear: even though it wasn’t their families who sat down and discussed terms, this was an arranged marriage. The couple had been picked to stop the ravages of the coronavirus. In a way, they were a sacrificial appeasement to G-d, who was thought to have brought on the pandemic.

The wedding was purposely not conducted in a synagogue, in a wedding hall or in someone’s house. The reasoning was that the community hoped that the souls of those interred in the cemetery would reward this act of marrying two orphans and intercede to block the evil decree. Perhaps, G-d would be induced to have pity on the couple and, by extension, halt the spread of disease.

The first record of a plague wedding goes back to 1831, in Russia, during a cholera pandemic. Another written reference to this type of ceremony dates to 1849, in Krakow, Poland. Another publication, from the early 20th century, deals with stories about Rabbi Elimelekh Weisblum of Lizhensk, who apparently arranged such a marriage in 1785, during a cholera outbreak. Some historians argue that the tradition is older still. In any case, the ritual became firmly entrenched in the Jewish communities of the Russian Empire during the 1892 cholera outbreak. (See Jeremy Brown’s comprehensive article, “The plague wedding,” at traditiononline.org/plague-weddings.)

Over time, the ceremonies became more elaborate. Hanna Wegrzynek writes of “several instances” where part of the cemetery was demarcated, symbolically closing off the affected area, so to speak. Some ceremonies were accompanied by feasts and dancing.

Brown notes that Eastern European Jews who resettled in the United States early in the 20th century brought the plague wedding custom with them. Across the country, during the Spanish flu epidemic (in which my own maternal grandfather almost died), desperate Jewish communities married off dozens of young couples. One of the most celebrated and widely reported plague weddings took place between Harry Rosenberg and Fanny Jacobs in October 1918 at a cemetery near Cobbs Creek in Philadelphia. The event was attended by more than 1,000 people. Unfortunately, genealogical research suggests that neither Harry nor Fanny survived the Spanish Flu, dying along with 50 million others.

In November 1918, Rose Schwartz and Abraham Lachterman were reportedly married in a similar ceremony in Winnipeg, Man.

Yizkor, or memorial, books of Jewish communities wiped out in the Holocaust record a number of black weddings. And three of the most famous 20th-century Yiddish and Hebrew writers make reference to plague weddings.

In 1945, I.B. Singer wrote about a cemetery wedding in his short story Gimpel the Fool: “It so happened that there was a dysentery epidemic…. The ceremony was held at the cemetery gates, near the little corpse-washing hut. The fellows got drunk. While the marriage contract was being drawn up I heard the most pious high rabbi ask, ‘Is the bride a widow or a divorced woman?’ And the sexton’s wife answered…. ‘Both a widow and divorced.’ It was a black moment for me. But what was I to do, run away from under the marriage canopy?”

S.Y. Agnon mentions such a wedding in his 1945 Only Yesterday – “and they’ve already held a wedding for two orphans on the Mount of Olives to stop the plague.”

This past summer, Jerusalem’s Khan Theatre performed a dramatic adaptation of I.L. Peretz’s 1909 short story In the Time of Pestilence, in which there is a discussion about orphans marrying during an outbreak. The theatre company performed the work at Hansen House, the site of a former hospital for people suffering from Hansen’s disease (also called leprosy).

Since the 1800s, when the first plague wedding was reported, there have been a number of global pandemics. In chronological order, they include cholera, bubonic plague, measles, Russian flu, Spanish flu, Asian flu, HIV/AIDS, SARS and COVID-19. (See “Pandemics That Changed History,” at history.com/topics/middle-ages/pandemics-timeline.)

Even though plague weddings don’t seem to be at all effective in stopping outbreaks of diseases, for the guests, at least, the ceremonies could be seen as a means of escape, for a short time, from worry and despair.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.