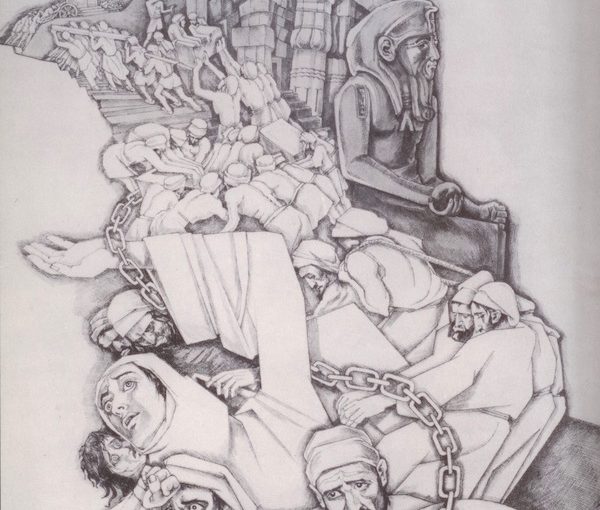

An image from the author’s 1941 Passover Haggadah by Saul Raskin.

Although they are not specifically mentioned in either the Haggadah or in the Torah, Egyptian pyramids have come to be associated with the Pesach story. That many modern Haggadot include illustrations of the pyramids points to how these structures play a key role in our collective memory.

At the Pesach seder, we say, “tze u l’mad,” “go out and learn.” In A Haggadah Happening, Rabbi Shlomo Riskin explains the idea as, “make sure your learning accompanies you wherever you go.” So what better way is there to appreciate the Hebrew slaves’ hardships than to visually present them by tangible symbols, such as the items on the seder plate, as well as the Four Sons, songs like “Ehad Mi Yodaya” (“Who Knows One”) and, of course, the pyramids?

But what specifically drew the Haggadah compilers to the pyramids? First of all, for a period of time, the Hebrews did live in Egypt. Thus, in Exodus, Chapter 5, we read about their involvement in Egyptian construction, where they are portrayed primarily as Egyptian brick-makers, not as builders: “‘Ye shall no more give the people straw to make brick, as heretofore. Let them go and gather straw for themselves.’ And the taskmasters of the people went out, and their officers, and they spoke to the people, saying: ‘Thus saith Pharaoh: “I will not give you straw.”’ So the people were scattered abroad throughout all the land of Egypt to gather stubble for straw. And the taskmasters were urgent, saying: ‘Fulfil your work, your daily task, as when there was straw.’”

Archeologists maintain that, in antiquity, Egyptian homes were constructed from mud bricks. Pyramids, however, were reportedly built of quarried, hewn stone and mud bricks. So, the more persuasive answer as to why modern Jews include pyramids in their Haggadot seems to be the pyramids’ sheer durability. That there are extant pyramids carries tremendous weight when retelling the story of the Hebrews’ time in Egypt – it connects us to our past.

Furthermore, that pyramids are still viewable is not a chance happening, apparently. According to freelance science writer Dr. Craig Freudenrich, the pharaohs built the pyramids knowing that the pyramid, with its square base and four equilateral triangular sides, is “the most structurally stable shape for projects involving large amounts of stone or masonry.”

Moreover, Donald Redford, a professor at Penn State University, reports that the ancient Egyptians probably chose that distinctive form for their pharaohs’ tombs because of their solar religion. The Egyptian sun god Ra, considered the father of all pharaohs, was said to have created himself from a pyramid-shaped mound of earth before creating all the other gods. The pyramid’s shape is thought to have symbolized the sun’s rays.

The shape of the pyramids was carefully chosen to reflect underlying aspects of divine unity. The pyramid has four faces: three faces to the heavens and one face to the earth. Architecture-by-astronomy was common in the ancient world, says archeoastronomer Giulio Magli. The Great Pyramid of Giza, for example, is aligned with amazing precision along the compass points, which would have required the use of the stars as reference points.

Three pyramids were built at Giza, and many smaller pyramids were constructed around the Nile Valley. The tallest of the Great Pyramids reaches nearly 500 feet into the sky and spans an area greater than 13 acres.

What is truly startling is that, with no connection to Egypt, other ancient cultures built pyramids in such far away places as Latin America and in what is, today, southern Illinois, in the United States. Like the ancient Egyptians, these other cultures understood the power and sway the pyramid structure had over the general population. According to history.com editors: “The Americas actually contain more pyramid structures than the rest of the planet combined. Civilizations like the Olmec, Maya, Aztec and Inca all built pyramids to house their deities, as well as to bury their kings. In many of their great city-states, temple-pyramids formed the centre of public life and were the site of holy rituals, including human sacrifice.”

While Egyptian pyramids are closely connected to the sun, Peruvian pyramids were considered to be replicas of mountains; they were thought to possess all the powers the mountains themselves possessed.

Twenty minutes away from St. Louis, Mo., are the remains of the United States’ first high-rises. They are more than 850 years old, constructed by the Cahokia Indians of Illinois. At 5,000 square feet, the house of the great chief or high priest (or another type of leader, since we really don’t know) was the most impressive of all the buildings. From the flat top of this colossus, with a footprint of 14 acres, it is larger at its base than the Great Pyramid of Khufu, Egypt’s largest.

So important is the pyramid as a symbol that it was used on the U.S. one dollar bill. According to the bill’s designer, the pyramid was used because it “signifies strength and duration … a new order of the ages.”

According to Bill Ellis, a professor emeritus of American studies at Penn State, “The pyramid was seen as the kind of human structure that lasted out the ages.” He said America’s Founding Fathers wanted the country to last as long as the pyramid – though the pyramid didn’t show up on the dollar bill until 1935, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s administration added them. “New order” is printed in Latin, under the pyramid, and historians say this refers to the birth of a new country and FDR liked the way it synced with his New Deal program.

Whether, in fact, the Hebrew slaves actually built the Egyptian pyramids is of secondary importance, as so many freedom struggles have been based on the tale that the Hebrews had to construct these mammoth buildings until they fled the slavery of Egypt.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.