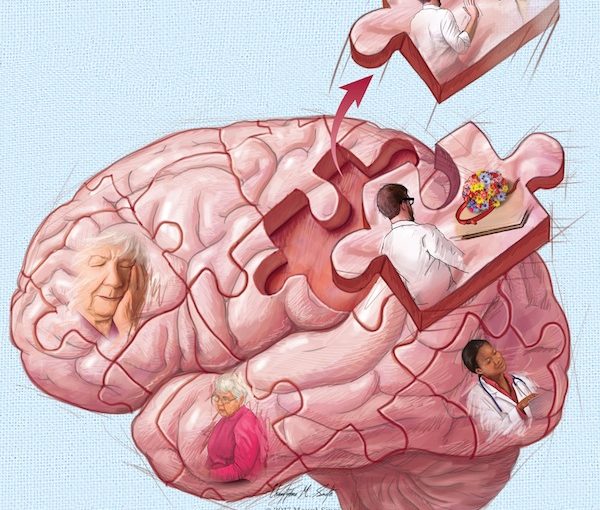

(printed with permission from ©Mount Sinai Health System)

To alleviate trauma victims’ suffering, specialists are working to reduce the emotion attached to painful memories. A leader in this field is Israeli-born scientist Daniela Schiller, who has been living in New York for the last 10 years, working as director of the Laboratory of Effective Neuroscience at Mount Sinai School of Medicine.

“I’m interested in emotions in general, because emotions can limit our freedom,” said Schiller, giving fear as an example. “It’s something that is very limiting. It’s like a dictator is taking over our brain and controlling our emotions, thoughts, decisions and behaviour.”

According to Schiller, we have the ability to change the emotions we experience, including when it comes to memories of trauma. “We have much more flexibility,” she said. “It’s a dynamic process and we can engage in that process.

“We used to think of this as a one-time process – memory creation – wherein you have them forever. In the ’60s, there was a hint that maybe it’s not a one-time process and that, actually, when you retrieve a memory, it might return to an unstable state, something similar to a newly formed memory. Then, it has to be stored again. It was termed ‘reconsolidation,’ because you repeat that process of storage.”

Schiller explained that returning a memory to an unstable state is a built-in mechanism that allows people to mix in new data about an event that happened. This built-in sensibility allows for better predictions in the future – it’s a survival system.

With the reconsolidation of memory becoming better understood, scientists are trying to find ways to use the process in real-life scenarios with trauma victims, including people suffering post-traumatic stress disorder. However, since the process also can be used to manipulate memory in a negative way, there are ethical questions that need to be addressed. At the recent Harvey Weinstein trial, for example, expert psychologist Elizabeth Loftus was called on behalf of the defence to explain how memory can change over time.

“You can easily influence eyewitness testimony when you do an investigation, by the way you ask questions and shake people’s memories,” explained Schiller. “You can plant information, and they will generally believe that this is what they remember.”

Loftus pointed to the fragility of memory, including the neurological basis to that effect, said Schiller. And, in her testimony, Loftus shared that the presence of mind-altering chemicals, like drugs and alcohol, can affect how memory is stored.

The research Schiller is conducting is geared to finding ways to lessen the emotional volume involved. “We want them to understand what happened, but the memories have to be manageable emotionally,” she said. “And the emotional advantage you had in your past or in your childhood, the emotions wear out, they become less and less emotional. Memory changes and, if it doesn’t, that means it’s a problem.”

Schiller speculated that many of the treatments that already exist capture only part of the process. For example, treatment with a therapist could be toward memory activation – meaning, you would be going into your traumatic memory. While you were in that memory, your therapist would work with you to change the emotional tone of it.

“In animals,” said Schiller, “we know the cellular processes that indicate memory is now moving and that it has been mobilized into a stable state where things are now happening and, now, you can either block it with a drug or with behaviour. We have very accurate measurements. But, with humans, we don’t know. We don’t know still what it means if the memory is actively stable in the brain. We speculate that, if you express it and you show emotions, it’s probably unstable. And then, you’d move forward and either get the drug or do behavioural therapy of some sort.

“For example, image extinction, wherein you think about the event and re-script it in a certain way, so it gives you the possibility to rewrite it – there are many different methods. There can be indirect methods that generate interference, like doing something else or using a blocker drug. These are all methods that can reactivate the memory.”

Although research on humans has shown some promise, Schiller said much more research is needed before any treatments can be developed. “We are still looking for the exact way to manipulate it to some degree, especially to tailor it to each individual,” she said.

What Schiller finds promising is that it’s a natural process – one that people practise every day, unconsciously. With that in mind, we should be able to find ways to do it consciously, by thinking about particular memories we want to rewrite and incorporate new information, she said. “Align yourself to reactivate it and try to incorporate it into the present. Again, this is not scientific advice on how to do it – this is what the science sees, the direction you can take.”

In studying the brain patterns of sleeping subjects who have experienced trauma, scientists have pinpointed where the subject’s memory was processing the parts of the trauma that induced emotion, causing bodily changes.

“They are unconscious to some extent, until they reach the conscious level and you have feelings and interpretations,” said Schiller. “That’s a whole different level and whole different process in the brain. So, we do need to look at these various levels, and then we need to adjust our therapy to these levels.

“I think it has deep meaning and I think it’s still within the scientific domain, but it will get interesting when these insights get more and more into the social realm and public awareness … because people tend to think of their memories as accurate, especially their emotional memories. I hope that the more we understand and the more science progresses, the more people will learn about it. And, the more it will change and give us flexibility, freedom, and more tools for change.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.