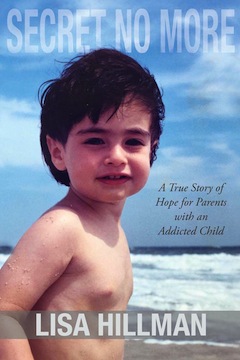

Left to right: Lisa, Jacob and Richard Hillman. (photo from Lisa Hillman)

“I had a fairly demanding and public position in the health system. I was president of our hospital foundation, had a very large board of about 25 people and a staff of about a dozen people. We were raising a lot of money to build a new hospital campus at the time, and so I was very public and very out and about. And, my fear was, as sick as it is to say today, that, if somebody would find out that my son had a drug problem, what would that say about me? What kind of mother could I be? What kind of person was I if I had a son who was using illicit drugs?” Lisa Hillman, author of Secret No More: A True Story of Hope for Parents with an Addicted Child, told the Independent.

“That was my feeling at the time,” she said. “I was not at all prepared to have addiction in my household. I was both ashamed and terrified at the same time.”

Hillman and her now-sober son, Jacob, shared their story at a Jewish Child and Family Service (JCFS) event at Congregation Shaarey Zedek in Winnipeg late last year.

Lisa and Richard raised their family in Annapolis, Md. Jacob was in high school when they found out he was using drugs. With almost 40 years of experience in the healthcare industry and being the healthcare decision-maker for the family, Lisa was determined to help Jacob overcome his addiction, while also keeping it a secret.

Like many others, however, she learned the hard way, after a couple of years, that this was not something she could fix. Although she held out hope that Jacob’s use of drugs was just a normal coming-of-age rite of passage, like trying cigarettes or alcohol, and that he would return to being the high-achieving person she knew him to be, that is not what happened.

“At first, we had him evaluated,” said Hillman. “I asked him if he would see a psychologist. He said ‘yes.’ He had bi-weekly meetings with a psychologist. At one point, my son gave me permission to talk to him – Jacob asked me, ‘If he tells you I’m alright, will you get off my back?’ And, I said, ‘sure.’

“This was when he was still in his senior year of high school. I visited with the psychologist, who said to me, ‘I told your son to smoke a little less.’”

Jacob was arrested during a holiday week after graduation, and the situation became more serious. As the family worked to get Jacob help, he resisted it, as addicts often do.

“The question I always get is, ‘How do you get them to accept treatment if they don’t want it?’” said Hillman. “I wish I had an answer for that. What we did with our son is finally say to him, ‘Jacob, you have a choice. You can continue to use, but you can’t live under our roof, or Dad and I will pay for inpatient treatment.’ Fortunately, he accepted inpatient treatment.

“Keep in mind, I’m very blessed,” she added. “I had some insurance and other resources. We were able to afford to send him someplace, which I know a lot of families can’t afford to do. I’m very, very lucky.”

The Hillmans found a place in Maryland, because Jacob did not want to leave the state. The place seemed to be very lovely and spiritual. They were hopeful he would get better there. But, after 12 days, the Hillmans visited their son and Lisa knew he had been using. Sure enough, the next day, Jacob’s counselor asked them to come pick Jacob up, that Jacob could no longer stay there.

“We brought him home to Annapolis,” Lisa Hillman said. “He entered the addiction treatment centre inpatient [program] that is part of my health system, where I was then and am still today, on the board. So, my drive for anonymity in this situation was about to crumble. The counselor my son was seeing said to me, ‘You have to tell somebody at work.’ So, I told my boss, the CEO of the hospital, and he was very empathetic and extremely understanding.”

Jacob went in for two weeks, after which the counselors suggested the Hillmans allow him to go to Florida for continued treatment, where he could live in a sober living house and continue to get outpatient treatment.

“The day he left, the counselor said to me, ‘Your son is going to have his program. What are you going to do for yourself?’” said Hillman. “My immediate reaction was that the counselor must have had 10 hits too many, because I didn’t have an addiction. I wasn’t the sick one, my son was the sick one. And yet, I realized I was crying all the time, I was obsessed with where he was and I couldn’t go to sleep at night until I knew he was home.

“I was isolated, I was depressed,” she said. “I wasn’t sharing anything with family and friends. So, I tried Al-Anon. And, from my very first time, I realized I’d [found] a home. These people understood me and were going through the same thing. I wasn’t alone anymore. I had people around me who got it and who were going through the same thing. Meanwhile, my son was in Florida and was getting better.”

Midway through that first year, Jacob had a minor relapse and told his parents about it over the phone. In that conversation, his mother said to him, “Jacob, we love you. Thank you for being honest and telling us. Please take care of yourself. You’re the only one who can.’ And Jacob replied, “Mom, thank you. That’s exactly what I needed to hear.”

Hillman recalled, “Pre-Al-Anon, I would have been on the phone screaming at him, angry. Fast-forward another six months, and he has another much more serious situation. We were told, ‘Your son needs detox.’ He was using heroin IV, a horrible scenario. So, we were asked to pay for a third inpatient treatment centre.

“I remember clearly asking the counselor, ‘How many times do we have to pay for this?’ And he said, ‘Tell your son that this is the last time.’ So, we did and, at the time, we did mean it, really. This was the last time we’d pay for him to have inpatient treatment.”

Although Hillman cannot say for sure that this ultimatum is what did it, Jacob stayed there for 100 days. After that, he moved, got a job and stayed for six months in a sober house. He kept the job for several years and eventually moved into an apartment. He has been active in AA ever since and has been clean for almost eight years.

Hillman has continued going to Al-Anon. She asked her husband to come with her and try it out at least once. They went to a different meeting than she had been going to. “We walked into the room and there were two couples who we know really well,” she said. “Both of them had children with similar problems and we had no idea. We’ve been going to that same meeting now for almost nine years, every Thursday night.

“That first meeting was a huge relief,” she said. “I couldn’t speak at the first meeting. I couldn’t open my mouth, with lips quivering as I cried. They let me cry. Other people at that meeting cried. And I heard a phrase that night, that I think really guided me: ‘Detach with love’ – meaning you have permission to detach from your loved one’s problems, that you’re not responsible for them, that you can’t fix their problems, but that you still love them.”

Hillman realized, over time, that Jacob would have to find his own way and that she couldn’t enable him by sending money or paying for things for him. “But, we never stopped loving him the whole way, the whole time,” she said.

As she healed, Hillman felt the desire to write a book about her experiences. She asked her son for permission to publish it.

As she healed, Hillman felt the desire to write a book about her experiences. She asked her son for permission to publish it.

“The reason for writing it was, I knew there were other families in hiding and ashamed, and that shame and fear just makes it worse,” she said. “It makes it worse for you if you love someone in addiction, and it doesn’t help the person with addiction. The whole purpose in writing this was to help particularly other moms and dads and sisters and brothers and boyfriends and aunts and uncles and grandfathers who I knew were sort of in hiding and had secrets and weren’t sharing – giving them hope that they can do it, too.

“Don’t hide,” she stressed. “Find professional help for yourself. My message is not to those with addiction, it’s to those who love people with addiction. My son says, ‘Mom, remind people that this is your story. Not mine.’

“If you have somebody in your life that is using or drinking, please go get help for yourself,” she said. “If one person in the family can get healthy and understand addiction, boundaries, and how to take care of themselves, then it will affect the rest of the family.

“That’s what happened in our family. I got stronger, my husband got stronger. Jacob saw that we were trying to understand him, that we were trying to get ourselves right again. He was getting better and we had a common language.”

Hillman said, “I think people who recover from an addiction and somehow live every day clean and healthy, year after year after year, to me, they are the most amazing, profound people. My son has become just an astonishingly profound young man and I’m very, very proud of him.

“I think that Judaism hasn’t helped us here today,” she added. “I think it’s getting better, but, looking back on it, part of my shame was that this doesn’t happen to Jews. We’re smart, educated, driven, are achievers, we don’t have addiction – but that’s not true.”

The Nov. 25 event with the Hillmans was sponsored by the JCFS and Gray Academy of Jewish Education. Panelists included an addictions physician, a therapist and an Addictions Foundation of Manitoba consultant on youth.

“Recovery is individual. There is no single treatment that works for everyone. There is no easy fix, like there is no single cause. It’s a combination of factors,” said Ivy Kopstein of the JCFS. “As a community, we need to end stigma and judgment, and replace it with compassion and understanding so we have no need for secrets anymore.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.