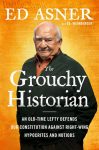

The gruff yet endearing Jewish character actor Ed Asner is instantly recognizable to many people for his portrayal of the equally gruff yet amiable Lou Grant in the classic 1970s television sitcom The Mary Tyler Moore Show and its spinoff drama Lou Grant. Fewer people realize that the Emmy Award-winning actor is also a well-known political activist, whose views became more prominent in the 1980s during his two terms as president of the Screen Actors Guild. Asner, now 88 and far from retirement – he just performed here in April in a one-man stage play – has written The Grouchy Historian: An Old-Time Lefty Defends Our Constitution Against Right-Wing Hypocrites and Nutjobs (Simon & Schuster, 2017) with Ed Weinberger, longtime screenwriter for The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

In this compelling read, Asner attempts – in his own words – to “reclaim the [U.S.] Constitution” from far-right conservative pundits. Making no secret of his ideological perspective, Asner argues, “The constitution is the cornerstone of the Republican party’s agenda, along with small government, less regulation and making sure the rich pay less taxes than the rest of us.” Yet, he maintains, the constitution was written to form a robust central government – giving sweeping powers to Congress (not the states) – secured by an equally strong executive branch. He further asserts, “Nothing in the constitution suggests, let alone enforces, the concepts of limited government, limited taxes and limited regulations.” Far from hating taxation, the framers of the constitution, writes Asner, desperately needed taxes because “[t]hey had a war to pay off.”

Asner notes that John Adams had wanted the presidential role to have even more powers by not requiring the “advice and consent” of the Senate to make federal and cabinet appointments, “a clear signal that Adams, like [Alexander] Hamilton, believed in a strong central government headed by an executive with vigorous powers.”

About the constitution’s founders and framers, Asner says they were “petty, flawed, inconsistent and all too human,” but, he concedes, they were highly educated “eloquent orators and brilliant writers,” who, “[u]nlike the current right-wing doomsayers and fearmongers, they were all, truly, apostles of optimism.”

Asner spends several chapters discussing God and the constitution – notably God’s absence from the preamble, as well as the Presidential Oath of Office – and speculates why the framers took their approach. He points out George Washington was a Grand Master Mason on whose Bible he took his oath of office, noting, “Masonic Bibles do not acknowledge the divinity of Jesus Christ.” As for Benjamin Franklin, Asner says, “you can quote endlessly about Franklin’s faith in Christian ethics, but none about his faith in Jesus the Christ.” Regarding Adams, Asner mentions that, as a member of the New England branch of the Unitarian Church, Adams and fellow “Unitarians did not believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ, the infallibility of the Bible, the Holy Trinity or Original Sin.” In other words, Asner takes a swipe at the Christian right who claim Christian origins for the American constitution. Asner points out that the entire career of James Madison Jr., as “a politician, lawmaker, intellectual – was devoted to the separation of church and state.” Yet Asner defends First Amendment rights for freedom of religion.

Not only does Asner explore in great detail the actual writing of the constitution and the financial backgrounds of all 55 delegates to the Constitutional Convention, but he does so in the gruff and thorough style of newsman Lou Grant. About these delegates – whom he claims conservative legal theory holds were “infallible patriots” who behaved “solely to establish national unity, economic development and the civil liberties of all citizens” – Asner concludes, “One thing is for certain: they are not the saints living in the imagination of the right wing, acting out God’s will.”

Asner notes that more than 40 delegates held government bonds, more than 15 were slave owners, and several were land and debt speculators. Most participated in more than one category, like Washington, who was not only “a slave owner [but] a money lender, a land speculator and the largest holder of government IOUs in the country.” Asner points out that small farmers, shopkeepers, labourers, Revolutionary War veterans and slaves, among others, were not at the convention. Hence, he paints a picture of a small group of “capitalist elites” with personal interests – two notable exceptions being Madison and Hamilton – who framed the constitution. In reaching his conclusions, Asner draws on the ideas of American historian Charles A. Beard’s admittedly controversial early 20th-century economic views of the document.

Asner shows his creativity in a humorous way, like in his “Open Letter to Senator Ted Cruz, Written in the Style of 1787,” where he states, “I am prompted to write this upon discovery of a foreword you penned to The U.S. Constitution for Dummies.” He proceeds to carefully address, in language of the day, five of Cruz’s assertions, after which he closes with “Whilst This Flame Exists Within Me, I Remain Your Most Staunch Adversary.”

Not many could pull this off as well as Asner. Same goes for his scathing review of the controversial personal and constitutional views of Dr. Ben Carson, neurosurgeon and secretary of housing and urban development. And Asner goes further in his criticism of such contemporary conservative social critics as Ann Coulter.

Asner critiques the origins of the Bill of Rights using language of the era in the inventive form of a series of letters from Madison to heighten the drama of the time. After all, as Asner correctly notes, “It is the Bill of Rights – guaranteeing our freedoms of speech, conscience, religion, and the press – that is the centrepiece of America’s exceptionalism.” However, he also argues its practical limitations over the centuries through a careful description of a series of legal cases.

Asner even shares his own set of constitutional amendments, both humorous and real, including his desire for a guaranteed minimum income, which he is careful to note was not just a liberal idea but was also advocated by conservative economist Milton Friedman and nearly implemented by Richard Nixon in the 1960s. Yet, for a self-declared “old-time lefty,” Asner surprises the reader with his qualified defence of the Second Amendment. He devotes an entire chapter to it.

Asner says he is “not against guns and the good people who own them.” He even admits to owning a Glock 15 – obtained for reasons of self-defence after receiving a death threat in 1979 – and a Beretta Px4, because he “liked its look and the heft of it” in his hand. However, he convincingly argues that American “gun culture” has led to too many deaths. He concedes, “It’s a bloody trail that leads right back to the Second Amendment,” specifically, “the right wing’s interpretation of it: an unfettered licence for every American to own, carry, collect, trade and eventually shoot a gun.” He maintains that this item in the Bill of Rights was not the clearest constitutional amendment ever written because, when it states the need for “a well-regulated militia,” that does not automatically imply a concurrent “personal right” for the individual citizen “to keep and bear arms.”

Asner takes this view from a close examination of the wording used by the framers of the constitution. “The only two subjects in the Second Amendment,” notes Asner, “are collective nouns: ‘state militia’ and ‘people.’” Asner asks, “where, then, can anyone find an individual right to own a weapon except as part of a ‘well-regulated militia’”? He maintains that, historically, Madison’s intent was to limit the Second Amendment “only to state militias” and that the United States was, in fact, “founded on gun control,” with a balance between gun ownership and the desire for public safety. He goes on to outline a very persuasive argument to support his case while emphasizing that “today, despite the evidence, the gun lobby has the chutzpah to claim that the Second Amendment belongs to them and them alone.” According to Asner, the issue boils down to whether the Second Amendment represents a fundamental or absolute right that cannot be limited nor regulated – Asner maintains the former view.

Ultimately, Asner feels it’s time to return to the kind of America its founders envisioned, including a “government that rules by reason, tempered with compassion and advanced by science,” that guarantees free speech and respects liberties for all while protecting its most vulnerable citizens.

Whether left, right or centrist, readers will learn much from Asner, who comprehensively studied the topic and arrived at a serious analysis along with amusing takes. Since his voice is heard throughout the book, it’s easy to imagine this tome being transformed into a one-man stage play some day. But no one could do it as well as Asner. As for why an award-winning actor like him would write about the U.S. Constitution, Asner states without equivocation, “Well, why not me? After all, I have played some of the smartest people ever seen on television.” Newsman Lou Grant would be the first to agree.

Arthur Wolak, PhD, is a freelance writer based in Vancouver and a member of the board of governors of Gratz College. He is author of The Development of Managerial Culture and Religion and Contemporary Management, available in hardcover and ebook formats from all online retailers.